This weekend I visited Beit Lehem and Khalil (Hebron) with some of the other students in my program. I saw a lot of things, some of them uplifting, but the majority of which were disheartening if not downright depressing. I’m not sure where to start, but I think I will start at the end and work backwards, because the end of the trip left the most lasting impression on me, by far.

After our tour of the Old City in Khalil, I split off from the rest of my group and returned to the souq with our guide, R. One of us was going to have to return separately anyway because there weren’t enough seats on the service we were using to legally pass through Israeli checkpoints (8 seats, 9 people), so I volunteered because I wanted to quiz our tour guide about the organization he works for, Holy Land Trust. I was planning on contacting HLT anyway, because I worked with their sister organization, Nonviolence International, in DC. So . . . R and I hung out a while, I think I made a new friend (he invited me to stay with him and his wife in Beit Lehem anytime) and then I caught a service headed from Khalil back to the Kalandia checkpoint.

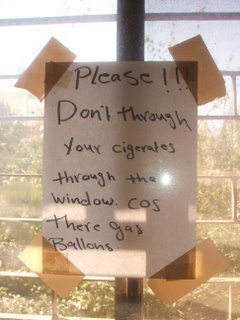

The ride was fairly uneventful until the end – me crammed in the middle seat and the middle row of a station wagon, with a elderly Palestinian woman dressed in traditional clothing on my right, and a large Palestinian man on my left trying desperately to stay far enough over on his side that there was no bodily contact between us. Our driver chain smoked, played with the radio station, and navigated the incredibly steep and dangerous road we careened along simultaneously. This is the only road open for travel to Kalandia without going though Jerusalem (which is forbidden for West Bank vehicles), and I have no idea how anyone navigates it in the winter . . . it is narrow with hairpin curves, no guardrails, and it is ridiculously steep. Just before we reached Kalandia we were stopped at a flying checkpoint (not a permanent checkpoint, just a place where an Israeli Army jeep pulls over and starts checking IDs. No one knows if there is any rhyme or reason to when and why they set up the flying checkpoints. . .

There were three soldiers with the jeep: one sitting in the jeep smoking and talking on his cell phone, one who came to our car and asked for everyone’s IDs, and one up high in the back of the jeep with a machine gun. From my seat, I could see a Palestinian kid they had already pulled out of another car, sitting on a rock next to the jeep. He was wearing a red long sleeved shirt and jeans, and had his back turned to the soldiers and angled away from the road. He was nervously fidgeting, wringing his hands, putting his head in his hands, and talking to himself (I can only assume he was praying). He was about 16 or 17 years old and looked completely terrified.

After a couple minutes, the soldiers pulled a young guy out of our car, probably about 22 or 23 years old, and told him to sit on the rock next to the other kid. Before getting out of the car, he reassured his family that he would be okay and told them to just leave him. Then the pulled out the man next to me, but he returned to the car after a couple minutes. The boy from our car looked less scared than the other kid, and his sister who was in seat behind me with his niece said he had already spent 5 years in an Israeli jail. After about 5-10 more minutes, the soldiers waved our car on, but because they still had the boy, the taxi driver pulled over just in front of the flying checkpoint. The driver got out of the car to smoke a cigarette, and we just sat there in total silence.

I also wanted a cigarette, so I decided to take a gamble and I got out of the car. I sat on a rock, not next to the boys, but close to them, and I pulled out a cigarette. I knew the soldiers knew that I was American because they had already looked at my passport. I looked over at the two boys, one still obviously scared, and the other quiet and I smiled at them both and nodded, they both nodded back. The soldier on the jeep with the machine gun was watching me, with his gun pointed at me during this 20 second interaction.

I took a deep breath, lit my cigarette, and settled onto the rock as if I was completely comfortable. I hadn’t even taken the second drag from my cigarette when the Israeli soldiers released the boy who had been in my car and told us to drive away. I hesitated for a second, because I didn’t want to leave the other boy by himself, but the taxi driver started yelling at me to hurry up. I hadn’t even gotten into the taxi before a second Israeli jeep pulled up (I assume border police, but I’m not sure), and we drove away.

Once I was back in the taxi and we had driven away from the checkpoint, everyone wanted to know my name, where I was from . . . They knew, as I did, that the Israelis had let the boy go (or at least let him go sooner) because I, an international, happened to be in their service and because I made my presence very obvious to the soldiers. They obviously hadn’t picked him up for anything in particular, because they wouldn’t have let him go so easily if he was actually wanted for some crime or political affiliation.

The sad part is, I didn’t even do anything. I just got out of the car and started to smoke a cigarette – exactly what I would do at home if my car broke down. I didn’t try to approach the soldiers, or the boys . . . I considered doing both of those things, but I was afraid that I would make the situation worse for the boys and I wasn’t sure what I could/should say that might have helped. I am repeatedly struck by the lack of rights and power that the Palestinians have, and that I, as a foreigner, have more influence than the average Palestinian citizen and resident. It also scares me, because with that power comes a responsibility that I feel very clearly. I don’t know if I handled that situation well, or if there are other, better things that I could have done. I can’t get the face of the boy in the red shirt out of my head. He was younger than my youngest brother, and he looked so scared but was trying to be brave at the same time.

I think that I am going to try and get some ISM training. I want to participate in the olive harvest, and I think that it would be a good idea to talk to more experienced people about how to handle these situations. If I have a clearer idea of what my rights are, and what the boundaries are for the soldiers, maybe I will be more effective – and less scared – the next time I find myself in this sort of situation. Unfortunately, I don’t doubt that I will find myself in these situations, regardless of whether or not I want to be in them. I think that it is privilege to help Palestinians in these situations -- and a responsibility -- but I want to do it in the most effective way possible . . .

I have a lot of other things to say about my trip to Beit Lehem and Khalil, but I think I will save it for another day.